Treatment, trials and ticking doctors off

Making treatment decisions isn't easy. Here's what we got right, what we got wrong and what we'd do differently if we had our time again.

Dad and I are sitting in a hospital waiting room for what feels like days but is in fact an hour. An hour is a long time when you’re waiting to be told your fate. We watch patients coming in and out; silently hunting for clues as to what our future might hold.

After an agonising wait, we sit opposite a world-leading Professor in Mesothelioma, filled with equal parts dread and hope. Dread she’ll deliver the worst of the worst news, and hope she’ll offer us a miraculous solution that might allow Dad to stay with us a little longer. As we start talking, I set my phone to voice record. I do this because I know when emotions are heightened, memory suffers.

“Are you recording me?!” she barks upon noticing, startling me and giving our long-awaited appointment an unfortunate start.

I stammer out a response that I am, but that I was just about to ask her permission. Internal me is screaming I DO THIS FOR A LIVING! I WOULD NEVER DISRESPECT YOU! I AM NOT AN IDIOT! But I can tell from her tone and body language that she has already decided I am not just an idiot, but a rude one at that.

I am hot and prickly and mortified. I pray for spontaneous evaporation but with no such luck am forced to remain in the room, in my body, and in my shame. I’ve been a health journalist for 15+ years, and now I had put myself in the position of not only looking stupid but undermining myself as Dad’s advocate. With my nervous system in full flight mode, I was anxious as hell about what we were about to hear and, for someone who asks questions for a living, was waiting for the ‘right moment’ to interject and ask the most important one up front: Do you mind if I record this so we can review it later? I’m worried I’ll forget the details.

Her heavy-handed response rattled me, making me more quiet and less self-assured than I’d usually be, given I was already armed with hours of research, pages of notes and dozens of questions. While I own the error, if her intention was to put me back in my box, she succeeded.

For the record, in most jurisdictions (Victoria, Queensland, the NT, NSW, ACT and Tasmania) patients don’t need permission to record their appointment with a doctor, nurse or other health professional if the recording is for their own use. In SA and WA, you usually need consent before recording. While I blundered this one, I would always ask, just because it’s the right thing to do and is conducive to a respectful patient-doctor relationship.

That appointment focused on treatment options, and the toolbox available to us to tackle this unlucky and cruel disease. The doctor, a senior consultant with many years of delivering bad news under her belt, worked methodically through our options: chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or, conveniently, a clinical trial she was spearheading testing combined chemotherapy and immunotherapy against chemotherapy alone to extend life for patients with mesothelioma, for which the prognosis was almost always poor. We were told Dad had a 50% chance of making it to a year, and that active treatment (meaning doing something about it) was his best chance of getting there.

Patients tend to do better in clinical trials because they get lots of attention – data is king in scientific publishing, and they ARE the data. Knowing this, and at my encouragement, Dad tentatively signed up. And if we had our time again? I don’t know if we’d choose the same.

If you or someone you love is faced with a treatment decision, here are the sources of information you’ll want to leverage to make an informed decision:

The experts: Specialists, like oncologists for example, deal with your disease or ones like it day in, day out. Their job is to give you your options, but you’re allowed to ask for their opinion. If they’re being cagey and won’t give it to you, reframe your question by saying things like: If you were me, what would you do?

The evidence: Ask your doctors if there are any good scientific papers, articles, podcast episodes or results of clinical trials they can point you to. And (for those who don’t speak fluent medical science) ask if they can walk you through them. a GP, psychologist or particularly health-literate friend might be better placed to do this with you than a time-poor specialist.

The experience: Lived experience is invaluable. While no two healthcare journeys are the same, speaking to someone who lives with the disease, has had the treatment or gone through the experience will hold value in a way the experts can’t deliver. Depending on your challenge, accessing those people may not be easy, so ask your doctors whether there are patient networks you might connect with, and failing that, hunt online or ask friends if they know of anyone you could reach out to.

In all Next Of Kin posts, you’ll find our best attempt at some ‘tips’. They are in no way exhaustive nor ground-breaking, but they’re the things we can put our finger on that helped (or would’ve) at that point in time, for what they’re worth.

Tips for navigating difficult doctors and decisions on treatment, from Casey’s perspective:

1. I’d highly recommend voice recording your appointments (most phones can do it) so you can listen back later, but make sure you ask permission up front. Simply say: ‘Do you mind if I record this so I can review it later? I’m worried I’ll forget some of the details.’ If they say no, tell them you’d like to be provided with detailed notes of the appointment, written in lay terms, and see how fast they change their tune. Failing that, just take copious notes.

2. Doctors are not gods, even when they’re world-class. I’ve interviewed hundreds of them and can tell you they all fail, falter and flub things sometimes. Not because they’re bad, but because they’re human. As such, you’ll need to give them some grace and, occasionally, some grief. Whether you’re in business class or cattle, they work for you – not the other way around.

3. When they say the system is patient-led, they are not f*cking around. It’s patient-led, patient-driven and patient-navigated. As such, the most important person to empower is… you guessed it, the patient. And the way to do that, as Next Of Kin, is to be their co-pilot. You’re not in charge, just walking beside them, holding their hand, advocating where needed or wanted and supporting where required. They’re Maverick, you’re Goose.

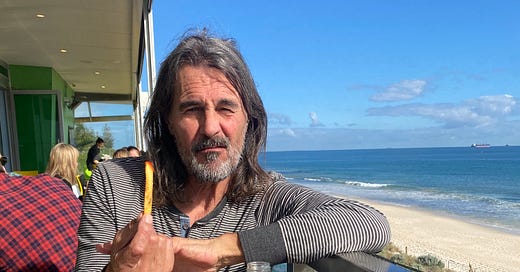

Next Of Kin is written by health journalist Casey Beros and her Dad, Jack Wilde, to create a space where patients and carers can become better Next Of Kin for each other and the world at large. If you know someone who would benefit from following our journey, please send this onto them. You can follow Casey on Instagram here and find out more about her work here.