Oh, the places we’ll go…

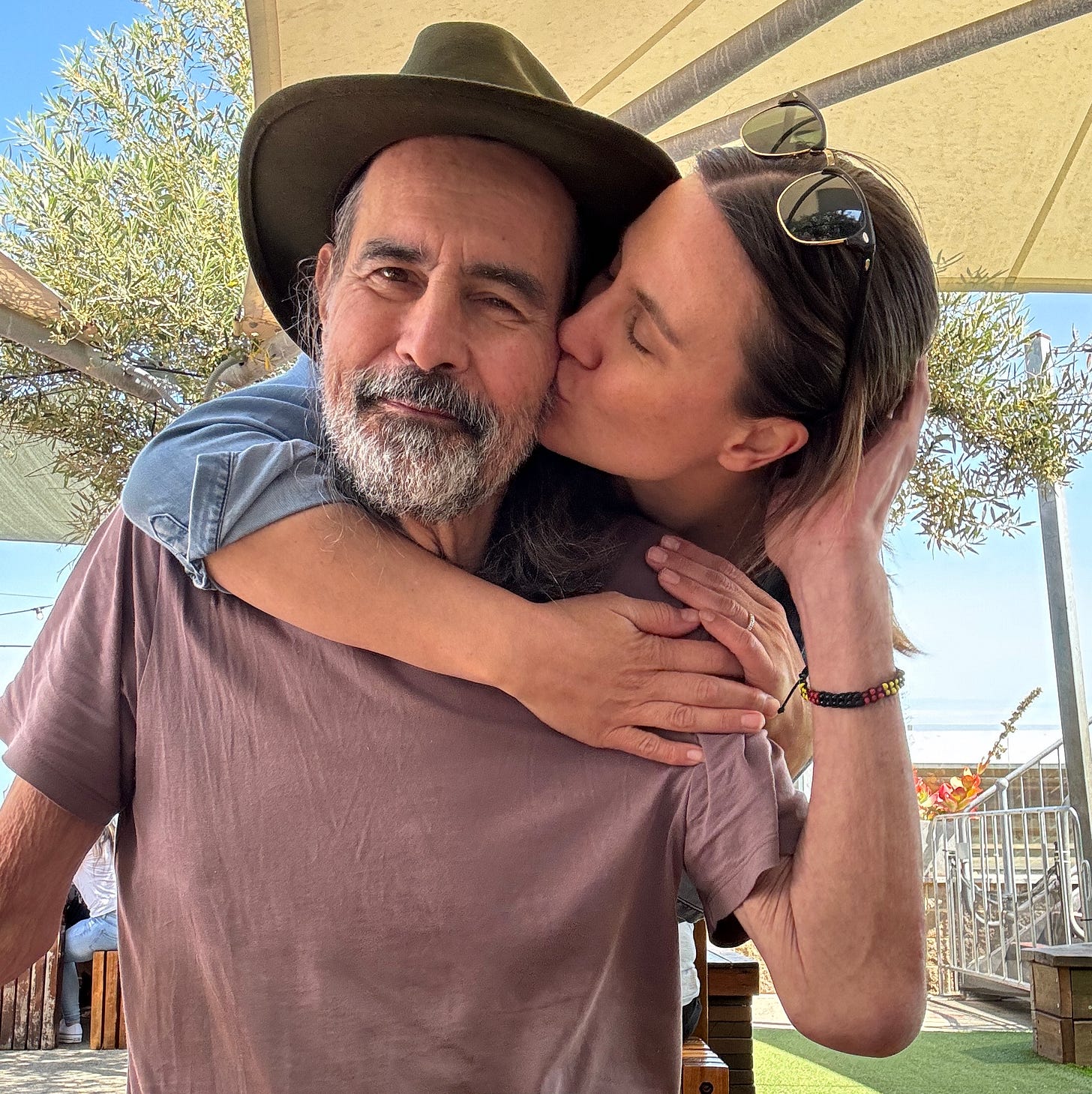

Big endings, new beginnings and missing people this Christmas.

I write to make sense of the world around me and share it in the hope it lights the path for someone following behind. But sitting down to capture the last few weeks feels crunchy – words failing to capture the magnitude of one of the biggest and toughest years of my life. I feel like I’m starting again; a fish out of water, a turtle without a shell or some other nonsensical aquatic analogy. So, from the depths of the ocean of my mind, here is my futile-but-trying attempt to capture what it’s like to lose one of your favourite people.

Let’s rewind to August, 2023. I take Dad for a scan, where he can barely stand from his wheelchair long enough to have his picture taken. After I help him sit back down, Dad puts his head on my chest. He isn’t stoic, he is sobbing. Small. Vulnerable. I don’t know what to say, so I say stupid things like; ‘it’s OK’ (it isn’t), ‘I’m sorry’ (I am) and ‘I love you’ (I do). Then, we move to a hospital consult room. I sit, he lays. We talk, we don’t. I read, he rests as we await the doctor and the news.

“The end of this disease has a sharp decline, it’s like standing on the edge of a cliff,” the respiratory doctor tells us. “Some people stand there for ages and it takes a big gust of wind to knock them off. For others, it’s a light breeze.”

We don’t know which weather he is forecasting for us, and for the first time I can remember in the last two-and-a-half years, Dad asks how long he has.

“Days or weeks, not months. Go home and spend time with your family and when you can’t manage at home anymore, come to the hospice.”

We leave in silence, driving past the beach on the way home because why not. I am hyper-vigilant, watching for clues into how the very worst news is landing on Dad. As we wind the streets on the short drive, we switch gears like Formula 1 drivers – from death and estate planning to local architecture and the weather. It feels, to me at least, strangely performative. M y mouth is conversing, but all my mind can hook onto is the thought that this might be my last Monday with Dad, ever.

Dad’s primary carer, I am exhausted. I’ve been ‘white knuckling’ through the last few months of caring for Dad as well as trying to mother, wife and work. The finish line is looming and, while my body knows it can’t keep going, my heart knows what the finish line means – a life without Dad. Dad doesn’t want to die so he pushes on, determined to outlive the death-sentence handed to him. And push on he does, for three more months where we get to walk, talk, think and be together. It’s precious and painful and beautiful and awful and monumental and mundane all at once. And then, even with two-and-a-half years to ‘prepare’ the end nears, and I am, in no way, prepared.

There is no word for the last month other than brutal. In a state of what’s known as terminal restlessness Dad cannot be still. It’s as though if he sits, sleeps or stops, death will catch him. So, we move. Day and night we walk anywhere and everywhere. When Dad’s feet are so swollen with fluid shoes no longer fit, we go barefoot. When his legs no longer work, I push him in the wheelchair. When getting out gets too much, we shuffle the hallway of his apartment. Up and back, up and back, up and back… his body desperate to surrender to a fate his mind won’t allow.

In the final days, I watch Dad’s prized mind fall apart. He wants to go to the butcher for mince. I say we will. He asks if my brother is coming with ‘the gear’. I say he is. He tries to eat my iPhone with a knife and fork. I silently replace it with a bowl of soup and spoon. He is quiet, frightened, and occasionally angry. The closest person to him, I bear the brunt of that anger, and while I try not to take it personally, it’s becoming impossible to separate the person from the disease. He feels ripped off, and I get it because I feel ripped off too.

WATCH: Dad and I get our ‘oh, the places we’ll go’ tattoos… via @caseyberos

In the final days nurses come to the house frequently to give Dad more and more medication – terminal sedation to allow his body to go through the process of death without causing his spirit too much distress. The medications get stronger and the doses get higher and eventually they insert a pump to deliver medication subcutaneously (through the skin), followed by a catheter to reduce the risk of falling on a trip to the bathroom.

Getting him into a restful state drains every last ounce of my wellbeing and makes my humanity wobble like jelly, as I balance the clear and medically informed need to get him comfortable with him not being ready to rest. On a particularly tough night, on not enough sleep and a steady diet of anxiety and Maltesers, I faint at 4am and smack my face on the metal hospital bed we’ve had delivered to the house, splitting my forehead and almost breaking my nose. I spend the morning in ED and come back with a glued-up face and a battle scar to rival Harry Potter.

That night, I get everyone to the house. Dad is sleeping now but complaining about it by breathing loudly – the ‘death rattle’ warning that the end is imminent. I’m certain he can hear us around the dinner table and is desperate to join us one last time. We’re all there – his Mum, kids, grandkids and his Death Doula. After dinner I go in to see him and can see his breath changing, like a tide slowly washing out. I take his hand in my hand, my other hand on his chest. He takes four big breaths, moving his head over his shoulder like he’s doing freestyle between the world he’s in and the one he’s heading to. Then he takes two smaller breaths and, with a quiet exhale, he is gone.

Watching someone you love die is heartbreaking but seeing them leave their broken body and suffering behind is painfully relieving. We open the windows so his soul can leave the room, then all put on his tee shirts and wash his body, talking to him as his skin changes colour and turns cool. My children kiss him goodbye and my husband takes them home so I can have one last sleepover with Dad.

He always told me that when you’re heartbroken you need to allow yourself to really feel it, to let the wind blow through the space where your heart used to be. Well Dad, it’s blowing a gale. There is a 6-foot-3, Dad-shaped hole in my heart that will never mend. But I know that - eventually - my heart will grow around it bigger and stronger… not because of losing you, but because I had you in the first place.

As a dear friend wrote to me on hearing the news:

There’s no way but through these huge things, I hope the ride has some warm spots.

I know it will as I move onwards, upwards, sideways and back again through grief and as I continue to spread the word about the beautiful, messy, complex job that is being Next Of Kin to each other – with Dad cheering me on from the best seats in the house.

My dear reader – if you’ve made it this far you deserve a medal (or at very least a cuppa and a snack). Next Of Kin will be back in 2024 with a brand-new slate of conversations about love, life, loss and who you'll be ‘Next’ for your eyes and ears. For anyone going through a tough time, a Next Of Kin subscription is the perfect gift that will deliver practical wisdoms to their inbox for the year – created and curated by me and gifted by you.

Thank you for being here, and for your patience with my recent silence as I’ve navigated the last few months – I am so grateful for you and can’t wait to share everything I have in store for you in the shiny new year.

Til then, hold your people tight this Christmas and give your Dad a hug from me.

Casey x

Next Of Kin is written by health journalist Casey Beros and her Dad, Jack Wilde, to create a space where patients and carers can become better Next Of Kin for each other and the world at large. If you know someone who would benefit from following our journey, please send this onto them. You can follow Casey on Instagram here and find out more about her work here.